- Published on

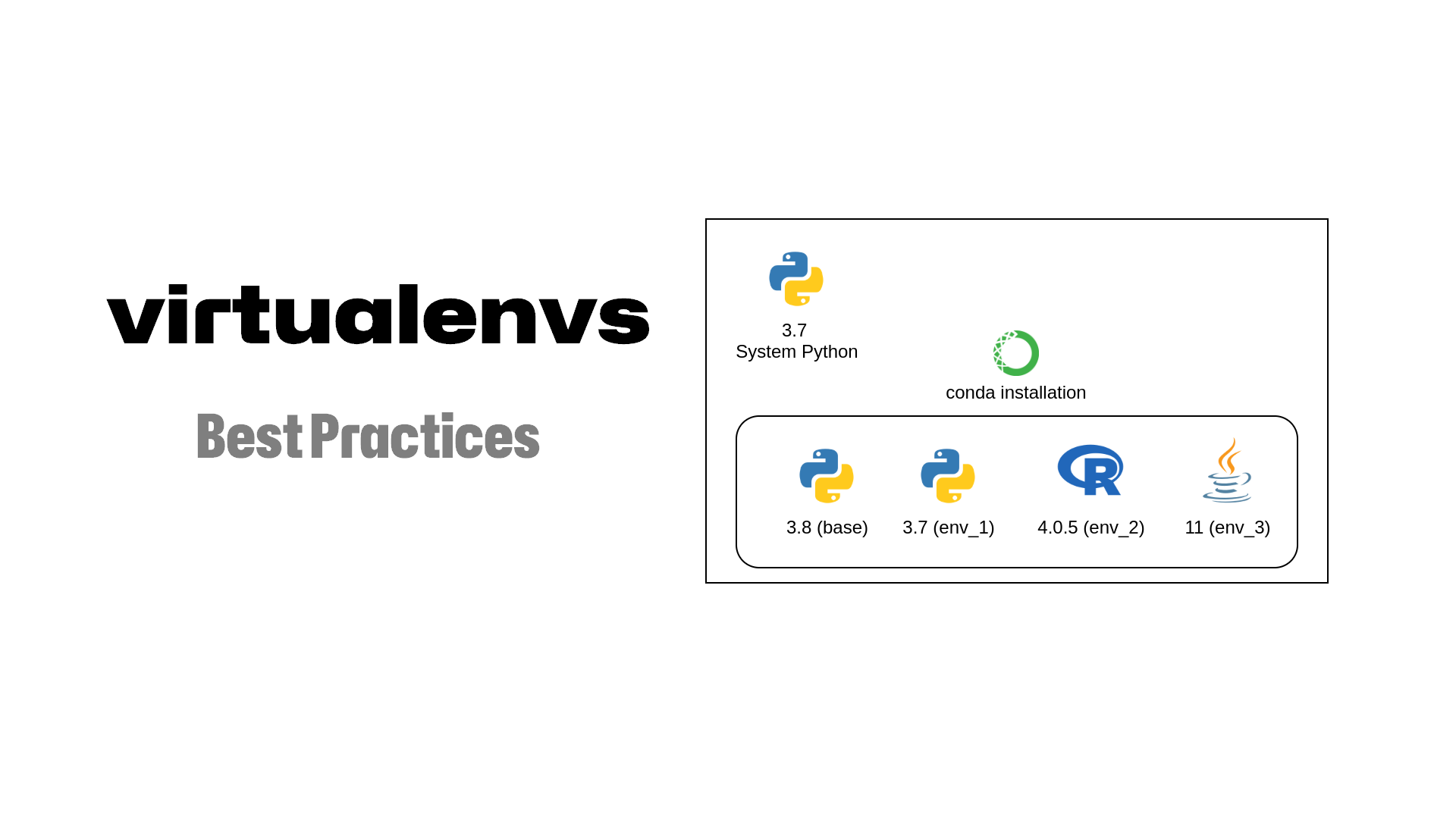

Best Practices with virtualenvs (Virtual Environments)

4 min read

- Authors

- Name

- Kiarash Soleimanzadeh

- https://go.kiarashs.ir/twitter

Let's explore the best practices in using virtual environments.

There is remarkably little advice on how best to manage your work with virtualenvs, though there are several sound tutorials: any good search engine gives you access to the most current ones. I can, however, offer a modest amount of advice that I hope will help you to get the most out of them.

Best Practices

Tip #1

When you are working with the same dependencies in multiple Python versions, it is useful to indicate the version in the environment name and use a common prefix. So for project mutex you might maintain environments called mutex_35 and mutex_27 for v3 and v2 development. When it’s obvious which Python is involved (and remember you see the environment name in your shell prompt), there’s less chance of testing with the wrong version. You maintain dependencies using common requirements to control resource installation in both.

Tip #2

Keep the requirements file(s) under source control, not the whole environment. Given the requirements file it’s easy to re-create a virtualenv, which depends only on the Python release and the requirements. You distribute your project, and let your consumers decide which version(s) of Python to run it on and create the appropriate (hopefully virtual) environment(s).

Tip #3

Keep your virtualenvs outside your project directories. This avoids the need to explicitly force source code control systems to ignore them. It really doesn’t matter where you store them—the virtualenvwrapper system keeps them all in a central location.

Tip #4

Your Python environment is independent of your process’s location in the filesystem. You can activate a virtual environment and then switch branches and move around a change-controlled source tree to use it wherever convenient.

Tip #5

To investigate a new module or package, create and activate a new virtualenv and then pip install the resources that interest you. You can play with this new environment to your heart’s content, confident in the knowledge that you won’t be installing rogue dependencies into other projects.

Tip #6

You may find that experiments in a virtualenv require installation of resources that aren’t currently project requirements. Rather than pollute your development environment, fork it: create a new virtualenv from the same requirements plus the testing functionality. Later, to make these changes permanent, use change control to merge your source and requirements changes back in from the fork.

Tip #7

If you are so inclined, you can create virtual environments based on debug builds of Python, giving you access to a wealth of instrumentation information about the performance of your Python code (and, of course, the interpreter).

Tip #8

Developing your virtual environment itself requires change control, and their ease of creation helps here too. Suppose that you recently released version 4.3 of a module, and you want to test your code with new versions of two of its dependencies. You could, with sufficient skill, persuade pip to replace the existing copies of dependencies in your existing virtualenv.

Tip #9

It’s much easier, though, to branch your project, update the requirements, and create an entirely new virtual environment based on the updated requirements. You still have the original virtualenv intact, and you can switch between virtualenvs to investigate specific aspects of any migration issues that might arise. Once you have adjusted your code so that all tests pass with the updated dependencies, you check in your code and requirement changes, and merge into version 4.4 to complete the update, advising your colleagues that your code is now ready for the updated versions of the dependencies.

Tip #10

Virtual environments won’t solve all of a Python programmer’s problems. Tools can always be made more sophisticated, or more general. But, by golly, they work, and we should take all the advantage of those that we can.