- Published on

Linear Algebra

266 min read

- Authors

- Name

- Kiarash Soleimanzadeh

- https://go.kiarashs.ir/twitter

Table of Contents

- Table of contents

- Preliminary concepts

- Sets

- Belonging and inclusion

- Set specification

- Ordered pairs

- Relations

- Functions

- Vectors

- Types of vectors

- Geometric vectors

- Polynomials

- Elements of R

- Zero vector, unit vector, and sparse vector

- Vector dimensions and coordinate system

- Basic vector operations

- Vector-vector addition

- Vector-scalar multiplication

- Linear combinations of vectors

- Vector-vector multiplication: dot product

- Vector space, span, and subspace

- Vector space

- Vector span

- Vector subspaces

- Linear dependence and independence

- Vector null space

- Vector norms

- Euclidean norm

- Manhattan norm

- Max norm

- Vector inner product, length, and distance.

- Vector angles and orthogonality

- Systems of linear equations

- Matrices

- Basic Matrix operations

- Matrix-matrix addition

- Matrix-scalar multiplication

- Matrix-vector multiplication: dot product

- Matrix-matrix multiplication

- Matrix identity

- Matrix inverse

- Matrix transpose

- Hadamard product

- Special matrices

- Rectangular matrix

- Square matrix

- Diagonal matrix

- Upper triangular matrix

- Lower triangular matrix

- Symmetric matrix

- Identity matrix

- Scalar matrix

- Null or zero matrix

- Echelon matrix

- Antidiagonal matrix

- Design matrix

- Matrices as systems of linear equations

- The four fundamental matrix subsapces

- The column space

- The row space

- The null space

- The null space of the transpose

- Solving systems of linear equations with Matrices

- Gaussian Elimination

- Gauss-Jordan Elimination

- Matrix basis and rank

- Matrix norm

- Frobenius norm

- Max norm

- Spectral norm

- Linear and affine mappings

- Linear mappings

- Examples of linear mappings

- Negation matrix

- Reversal matrix

- Examples of nonlinear mappings

- Norms

- Translation

- Affine mappings

- Affine combination of vectors

- Affine span

- Affine space and subspace

- Affine mappings using the augmented matrix

- Special linear mappings

- Scaling

- Reflection

- Shear

- Rotation

- Projections

- Projections onto lines

- Projections onto general subspaces

- Projections as approximate solutions to systems of linear equations

- Matrix decompositions

- LU decomposition

- Elementary matrices

- The inverse of elementary matrices

- LU decomposition as Gaussian Elimination

- LU decomposition with pivoting

- QR decomposition

- Orthonormal basis

- Orthonormal basis transpose

- Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization

- QR decomposition as Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization

- Determinant

- Determinant as measures of volume

- The 2 X 2 determinant

- The N X N determinant

- Determinants as scaling factors

- The importance of determinants

- Eigenthings

- Change of basis

- Eigenvectors, Eigenvalues and Eigenspaces

- Trace and determinant with eigenvalues

- Eigendecomposition

- Eigenbasis are a good basis

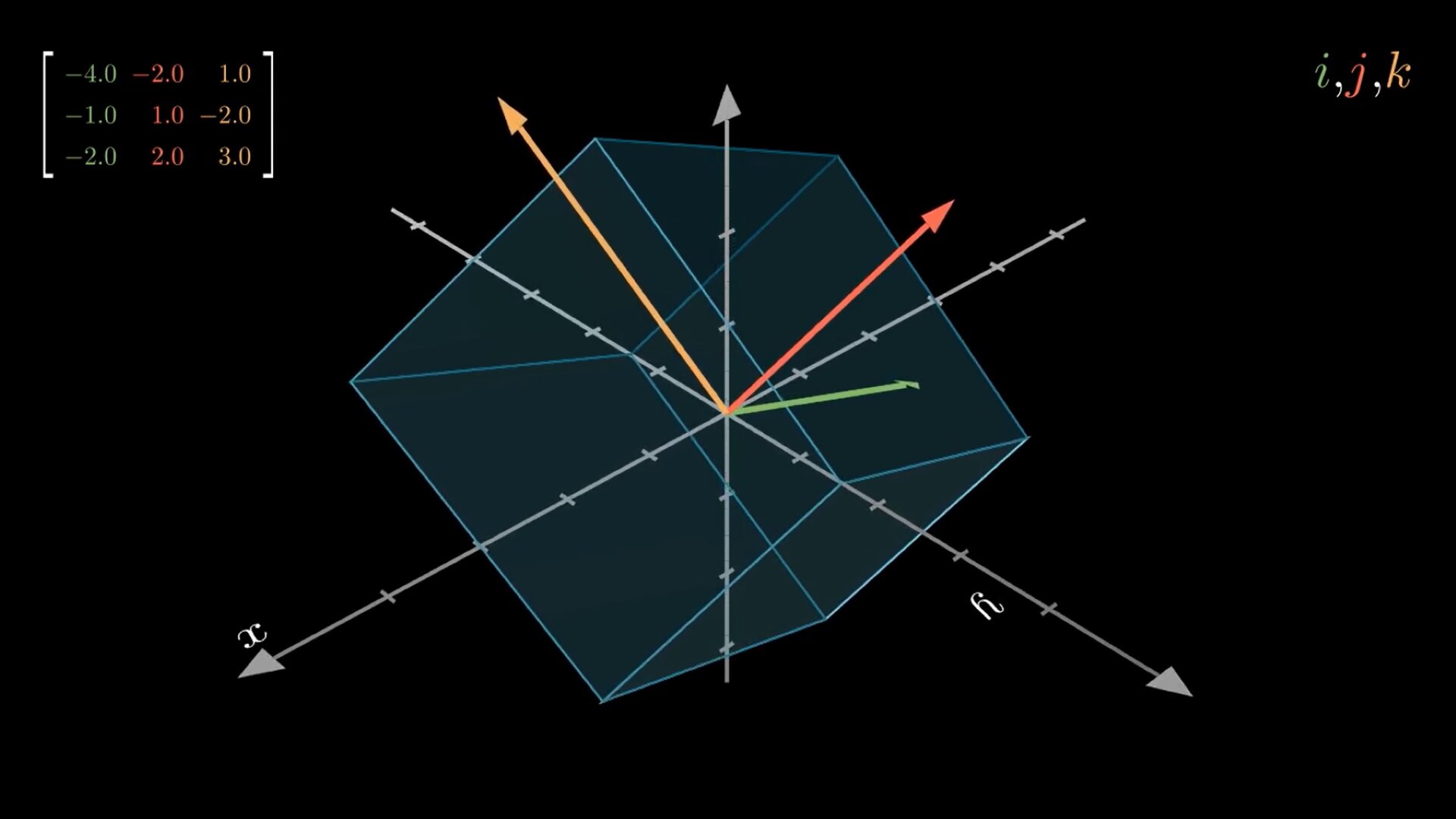

- Geometric interpretation of Eigendecomposition

- The problem with Eigendecomposition

- Singular Value Decomposition

- Singular Value Decomposition Theorem

- Singular Value Decomposition computation

- Geometric interpretation of the Singular Value Decomposition

- Singular Value Decomposition vs Eigendecomposition

- Matrix Approximation

- Best rank-k approximation with SVD

- Best low-rank approximation as a minimization problem

- Some notes

- Notation

- Linearity

- Matrix properties

- Matrix calc

- Norms

- Vector norms

- Matrix norms

- Eigenstuff

- Eigenvalues intro - strang 5.1

- Strang 5.2 - diagonalization

- Strang 6.3 - singular value decomposition

- Strang 5.3 - difference eqs and power A^k

- Epilogue

Linear algebra is to machine learning as flour to bakery: every machine learning model is based in linear algebra, as every cake is based in flour. It is not the only ingredient, of course. Machine learning models need vector calculus, probability, and optimization, as cakes need sugar, eggs, and butter. Applied machine learning, like bakery, is essentially about combining these mathematical ingredients in clever ways to create useful (tasty?) models.

This document contains introductory level linear algebra notes for applied machine learning. It is meant as a reference rather than a comprehensive review. If you ever get confused by matrix multiplication, don't remember what was the norm, or the conditions for linear independence, this can serve as a quick reference. It also a good introduction for people that don't need a deep understanding of linear algebra, but still want to learn about the fundamentals to read about machine learning or to use pre-packaged machine learning solutions. Further, it is a good source for people that learned linear algebra a while ago and need a refresher.

These notes are based in a series of (mostly) freely available textbooks, video lectures, and classes I've read, watched and taken in the past. If you want to obtain a deeper understanding or to find exercises for each topic, you may want to consult those sources directly.

Free resources:

- Mathematics for Machine Learning by Deisenroth, Faisal, and Ong. 1st Ed. Book link.

- Introduction to Applied Linear Algebra by Boyd and Vandenberghe. 1sr Ed. Book link

- Linear Algebra Ch. in Deep Learning by Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville. 1st Ed. Chapter link.

- Linear Algebra Ch. in Dive into Deep Learning by Zhang, Lipton, Li, And Smola. Chapter link.

- Prof. Pavel Grinfeld's Linear Algebra Lectures at Lemma. Videos link.

- Prof. Gilbert Strang's Linear Algebra Lectures at MIT. Videos link.

- Salman Khan's Linear Algebra Lectures at Khan Academy. Videos link.

- 3blue1brown's Linear Algebra Series at YouTube. Videos link.

Not-free resources:

- Introduction to Linear Algebra by Gilbert Strang. 5th Ed. Book link.

- No Bullshit Guide to Linear Algebra by Ivan Savov. 2nd Ed. Book Link.

I've consulted all these resources at one point or another. Pavel Grinfeld's lectures are my absolute favorites. Salman Khan's lectures are really good for absolute beginners (they are long though). The famous 3blue1brown series in linear algebra is delightful to watch and to get a solid high-level view of linear algebra.

If you have to pic one book, I'd pic Boyd's and Vandenberghe's Intro to applied linear algebra, as it is the most beginner friendly book on linear algebra I've encounter. Every aspect of the notation is clearly explained and pretty much all the key content for applied machine learning is covered. The Linear Algebra Chapter in Goodfellow et al is a nice and concise introduction, but it may require some previous exposure to linear algebra concepts. Deisenroth et all book is probably the best and most comprehensive source for linear algebra for machine learning I've found, although it assumes that you are good at reading math (and at math more generally). Savov's book it's also great for beginners but requires time to digest. Professor Strang lectures are great too but I won't recommend it for absolute beginners.

I'll do my best to keep notation consistent. Nevertheless, learning to adjust to changing or inconsistent notation is a useful skill, since most authors will use their own preferred notation, and everyone seems to think that its/his/her own notation is better.

To make everything more dynamic and practical, I'll introduce bits of Python code to exemplify each mathematical operation (when possible) with NumPy, which is the facto standard package for scientific computing in Python.

Finally, keep in mind this is created by a non-mathematician for (mostly) non-mathematicians. I wrote this as if I were talking to myself or a dear friend, which explains why my writing is sometimes conversational and informal.

If you find any mistake in notes feel free to reach me, so I can correct the issue.

Table of contents

Note: underlined sections are the newest sections and/or corrected ones.

- Types of vectors

- Zero vector, unit vector, and sparse vector

- Vector dimensions and coordinate system

- Basic vector operations

- Vector space, span, and subspace

- Linear dependence and independence

- Vector null space

- Vector norms

- Vector inner product, length, and distance

- Vector angles and orthogonality

- Systems of linear equations

- Basic matrix operations

- Special matrices

- Matrices as systems of linear equations

- The four fundamental matrix subsapces

- Solving systems of linear equations with matrices

- Matrix basis and rank

- Matrix norm

- Linear mappings

- Examples of linear mappings

- Examples of nonlinear mappings

- Affine mappings

- Special linear mappings

- Projections

- LU decomposition

- QR decomposition

- Determinant

- Eigenthings

- Singular Value Decomposition:

- Matrix Approximation:

- Some notes

Preliminary concepts

While writing about linear mappings, I realized the importance of having a basic understanding of a few concepts before approaching the study of linear algebra. If you are like me, you may not have formal mathematical training beyond high school. If so, I encourage you to read this section and spent some time wrapping your head around these concepts before going over the linear algebra content (otherwise, you might prefer to skip this part). I believe that reviewing these concepts is of great help to understand the notation, which in my experience is one of the main barriers to understand mathematics for nonmathematicians: we are nonnative speakers, so we are continuously building up our vocabulary. I'll keep this section very short, as is not the focus of this mini-course.

For this section, my notes are based on readings of:

- Geometric transformations (Vol. 1) (1966) by Modenov & Parkhomenko

- Naive Set Theory (1960) by P.R. Halmos

- Abstract Algebra: Theory and Applications (2016) by Judson & Beeer. Book link

Sets

Sets are one of the most fundamental concepts in mathematics. They are so fundamentals that they are not defined in terms of anything else. On the contrary, other branches of mathematics are defined in terms of sets, including linear algebra. Put simply, sets are well-defined collections of objects. Such objects are called elements or members of the set. The crew of a ship, a caravan of camels, and the LA Lakers roster, are all examples of sets. The captain of the ship, the first camel in the caravan, and LeBron James are all examples of "members" or "elements" of their corresponding sets. We denote a set with an upper case italic letter as . In the context of linear algebra, we say that a line is a set of points, and the set of all lines in the plane is a set of sets. Similarly, we can say that vectors are sets of points, and matrices sets of vectors.

Belonging and inclusion

We build sets using the notion of belonging. We denote that belongs (or is an element or member of) to with the Greek letter epsilon as:

Another important idea is inclusion, which allow us to build subsets. Consider sets and . When every element of is an element of , we say that is a subset of , or that includes . The notation is:

or

Belonging and inclusion are derived from axion of extension: two sets are equal if and only if they have the same elements. This axiom may sound trivially obvious but is necessary to make belonging and inclusion rigorous.

Set specification

In general, anything we assert about the elements of a set results in generating a subset. In other words, asserting things about sets is a way to manufacture subsets. Take as an example the set of all dogs, that I'll denote as . I can assert now " is black". Such an assertion is true for some members of the set of all dogs and false for others. Hence, such a sentence, evaluated for all member of , generates a subset: the set of all black dogs. This is denoted as:

or

The colon () or vertical bar () read as "such that". Therefore, we can read the above expression as: all elements of in such that is black. And that's how we obtain the set from .

Set generation, as defined before, depends on the axiom of specification: to every set and to every condition there corresponds a set whose elements are exactly those elements for which holds.

A condition is any sentence or assertion about elements of . Valid sentences are either of belonging or equality. When we combine belonging and equality assertions with logic operators (not, if, and or, etc), we can build any legal set.

Ordered pairs

Pairs of sets come in two flavors: unordered and ordered. We care about pairs of sets as we need them to define a notion of relations and functions (from here I'll denote sets with lower-case for convenience, but keep in mind we're still talking about sets).

Consider a pair of sets and . An unordered pair is a set whose elements are , and . Therefore, presentation order does not matter, the set is the same.

In machine learning, we usually do care about presentation order. For this, we need to define an ordered pair (I'll introduce this at an intuitive level, to avoid to introduce too many new concepts). An ordered pair is denoted as , with as the first coordinate and as the second coordinate. A valid ordered pair has the property that .

Relations

From ordered pairs, we can derive the idea of relations among sets or between elements and sets. Relations can be binary, ternary, quaternary, or N-ary. Here we are just concerned with binary relationships. In set theory, relations are defined as sets of ordered pairs, and denoted as . Hence, we can express the relation between and as:

Further, for any , there exist and such that .

From the definition of , we can obtain the notions of domain and range. The domain is a set defined as:

This reads as: the values of such that for at least one element of , has a relation with .

The range is a set defined as:

This reads: the set formed by the values of such that at least one element of , has a relation with .

Functions

Consider a pair of sets and . We say that a function from to is relation such that:

- and

- such that for each there is a unique element of with

More informally, we say that a function "transform" or "maps" or "sends" onto , and for each "argument" there is a unique value that "assummes" or "takes".

We typically denote a relation or function or transformation or mapping from X onto Y as:

or

The simples way to see the effect of this definition of a function is with a chart. In Fig. 1, the left-pane shows a valid function, i.e., each value maps uniquely onto one value of . The right-pane is not a function, since each value maps onto multiple values of .

For , the domain of equals to , but the range does not necessarily equals to . Just recall that the range includes only the elements for which has a relation with .

The ultimate goal of machine learning is learning functions from data, i.e., transformations or mappings from the domain onto the range of a function. This may sound simplistic, but it's true. The domain is usually a vector (or set) of variables or features mapping onto a vector of target values. Finally, I want to emphasize that in machine learning the words transformation and mapping are used interchangeably, but both just mean function.

This is all I'll cover about sets and functions. My goals were just to introduce: (1) the concept of a set, (2) basic set notation, (3) how sets are generated, (4) how sets allow the definition of functions, (5) the concept of a function. Set theory is a monumental field, but there is no need to learn everything about sets to understand linear algebra. Halmo's Naive set theory (not free, but you can find a copy for ~\10 US) is a fantastic book for people that just need to understand the most fundamental ideas in a relatively informal manner.

# Libraries for this section

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import altair as alt

alt.themes.enable('dark')

# ThemeRegistry.enable('dark')

Vectors

Linear algebra is the study of vectors. At the most general level, vectors are ordered finite lists of numbers. Vectors are the most fundamental mathematical object in machine learning. We use them to represent attributes of entities: age, sex, test scores, etc. We represent vectors by a bold lower-case letter like or as a lower-case letter with an arrow on top like .

Vectors are a type of mathematical object that can be added together and/or multiplied by a number to obtain another object of the same kind. For instance, if we have a vector and a second vector , we can add them together and obtain a third vector . We can also multiply to obtain , again, a vector. This is what we mean by the same kind: the returning object is still a vector.

Types of vectors

Vectors come in three flavors: (1) geometric vectors, (2) polynomials, (3) and elements of space. We will defined each one next.

Geometric vectors

Geometric vectors are oriented segments. Therse are the kind of vectors you probably learned about in high-school physics and geometry. Many linear algebra concepts come from the geometric point of view of vectors: space, plane, distance, etc.

Polynomials

A polynomial is an expression like . This is, a expression adding multiple "terms" (nomials). Polynomials are vectors because they meet the definition of a vector: they can be added together to get another polynomial, and they can be multiplied together to get another polynomial.

Elements of R

Elements of are sets of real numbers. This type of representation is arguably the most important for applied machine learning. It is how data is commonly represented in computers to build machine learning models. For instance, a vector in takes the shape of:

Indicating that it contains three dimensions.

In NumPy vectors are represented as n-dimensional arrays. To create a vector in :

x = np.array([[1],

[2],

[3]])

We can inspect the vector shape by:

x.shape # (3 dimensions, 1 element on each)

# (3, 1)

print(f'A 3-dimensional vector:\n{x}')

"""

A 3-dimensional vector:

[[1]

[2]

[3]]

"""

Zero vector, unit vector, and sparse vector

There are a couple of "special" vectors worth to remember as they will be mentioned frequently on applied linear algebra: (1) zero vector, (2) unit vector, (3) sparse vectors

Zero vectors, are vectors composed of zeros, and zeros only. It is common to see this vector denoted as simply , regardless of the dimensionality. Hence, you may see a 3-dimensional or 10-dimensional with all entries equal to 0, refered as "the 0" vector. For instance:

Unit vectors, are vectors composed of a single element equal to one, and the rest to zero. Unit vectors are important to understand applications like norms. For instance, , , and are unit vectors:

Sparse vectors, are vectors with most of its elements equal to zero. We denote the number of nonzero elements of a vector as . The sparser possible vector is the zero vector. Sparse vectors are common in machine learning applications and often require some type of method to deal with them effectively.

Vector dimensions and coordinate system

Vectors can have any number of dimensions. The most common are the 2-dimensional cartesian plane, and the 3-dimensional space. Vectors in 2 and 3 dimensions are used often for pedgagogical purposes since we can visualize them as geometric vectors. Nevetheless, most problems in machine learning entail more dimensions, sometiome hundreds or thousands of dimensions. The notation for a vector of arbitrary dimensions, is:

Vectors dimensions map into coordinate systems or perpendicular axes. Coordinate systems have an origin at , hence, when we define a vector:

we are saying: starting from the origin, move 3 units in the 1st perpendicular axis, 2 units in the 2nd perpendicular axis, and 1 unit in the 3rd perpendicular axis. We will see later that when we have a set of perpendicular axes we obtain the basis of a vector space.

Basic vector operations

Vector-vector addition

We used vector-vector addition to define vectors without defining vector-vector addition. Vector-vector addition is an element-wise operation, only defined for vectors of the same size (i.e., number of elements). Consider two vectors of the same size, then:

For instance:

Vector addition has a series of fundamental properties worth mentioning:

- Commutativity:

- Associativity:

- Adding the zero vector has no effect:

- Substracting a vector from itself returns the zero vector:

In NumPy, we add two vectors of the same with the + operator or the add method:

x = y = np.array([[1],

[2],

[3]])

x + y

"""

array([[2],

[4],

[6]])

"""

np.add(x,y)

"""

array([[2],

[4],

[6]])

"""

Vector-scalar multiplication

Vector-scalar multiplication is an element-wise operation. It's defined as:

Consider and :

Vector-scalar multiplication satisfies a series of important properties:

- Associativity:

- Left-distributive property:

- Right-distributive property:

- Right-distributive property for vector addition:

In NumPy, we compute scalar-vector multiplication with the * operator:

alpha = 2

x = np.array([[1],

[2],

[3]])

alpha * x

"""

array([[2],

[4],

[6]])

"""

Linear combinations of vectors

There are only two legal operations with vectors in linear algebra: addition and multiplication by numbers. When we combine those, we get a linear combination.

Consider , , , and .

We obtain:

Another way to express linear combinations you'll see often is with summation notation. Consider a set of vectors and scalars , then:

Note that means "is defined as".

Linear combinations are the most fundamental operation in linear algebra. Everything in linear algebra results from linear combinations. For instance, linear regression is a linear combination of vectors. Fig. 2 shows an example of how adding two geometrical vectors looks like for intuition.

In NumPy, we do linear combinations as:

a, b = 2, 3

x , y = np.array([[2],[3]]), np.array([[4], [5]])

a*x + b*y

"""

array([[16],

[21]])

"""

Vector-vector multiplication: dot product

We covered vector addition and multiplication by scalars. Now I will define vector-vector multiplication, commonly known as a dot product or inner product. The dot product of and is defined as:

Where the superscript denotes the transpose of the vector. Transposing a vector just means to "flip" the column vector to a row vector counterclockwise. For instance:

Dot products are so important in machine learning, that after a while they become second nature for practitioners.

To multiply two vectors with dimensions (rows=2, cols=1) in Numpy, we need to transpose the first vector at using the @ operator:

x, y = np.array([[-2],[2]]), np.array([[4],[-3]])

x.T @ y

# array([[-14]])

Vector space, span, and subspace

Vector space

In its more general form, a vector space, also known as linear space, is a collection of objects that follow the rules defined for vectors in . We mentioned those rules when we defined vectors: they can be added together and multiplied by scalars, and return vectors of the same type. More colloquially, a vector space is the set of proper vectors and all possible linear combinatios of the vector set. In addition, vector addition and multiplication must follow these eight rules:

- commutativity:

- associativity:

- unique zero vector such that:

- there is a unique vector such that

- identity element of scalar multiplication:

- distributivity of scalar multiplication w.r.t vector addition:

In my experience remembering these properties is not really important, but it's good to know that such rules exist.

Vector span

Consider the vectors and and the scalars and . If we take all possible linear combinations of we would obtain the span of such vectors. This is easier to grasp when you think about geometric vectors. If our vectors and point into different directions in the 2-dimensional space, we get that the is equal to the entire 2-dimensional plane, as shown in the middle-pane in Fig. 5. Just imagine having an unlimited number of two types of sticks: one pointing vertically, and one pointing horizontally. Now, you can reach any point in the 2-dimensional space by simply combining the necessary number of vertical and horizontal sticks (including taking fractions of sticks).

What would happen if the vectors point in the same direction? Now, if you combine them, you just can span a line, as shown in the left-pane in Fig. 5. If you have ever heard of the term "multicollinearity", it's closely related to this issue: when two variables are "colinear" they are pointing in the same direction, hence they provide redundant information, so can drop one without information loss.

With three vectors pointing into different directions, we can span the entire 3-dimensional space or a hyper-plane, as in the right-pane of Fig. 5. Note that the sphere is just meant as a 3-D reference, not as a limit.

Four vectors pointing into different directions will span the 4-dimensional space, and so on. From here our geometrical intuition can't help us. This is an example of how linear algebra can describe the behavior of vectors beyond our basics intuitions.

Vector subspaces

A vector subspace (or linear subspace) is a vector space that lies within a larger vector space. These are also known as linear subspaces. Consider a subspace . For a vector to be a valid subspace it has to meet three conditions:

- Contains the zero vector,

- Closure under multiplication,

- Closure under addition,

Intuitively, you can think in closure as being unable to "jump out" from space into another. A pair of vectors laying flat in the 2-dimensional space, can't, by either addition or multiplication, "jump out" into the 3-dimensional space.

Consider the following questions: Is a valid subspace of ? Let's evaluate on the three conditions:

Contains the zero vector: it does. Remember that the span of a vector are all linear combinations of such a vector. Therefore, we can simply multiply by to get :

Closure under multiplication implies that if take any vector belonging to and multiply by any real scalar , the resulting vector stays within the span of . Algebraically is easy to see that we can multiply by any scalar , and the resulting vector remains in the 2-dimensional plane (i.e., the span of ).

Closure under addition implies that if we add together any vectors belonging to , the resulting vector remains within the span of . Again, algebraically is clear that if we add + , the resulting vector will remain in . There is no way to get to or or any space outside the two-dimensional plane by adding multiple times.

Linear dependence and independence

The left-pane shows a triplet of linearly dependent vectors, whereas the right-pane shows a triplet of linearly independent vectors.

A set of vectors is linearly dependent if at least one vector can be obtained as a linear combination of other vectors in the set. As you can see in the left pane, we can combine vectors and to obtain .

There is more rigurous (but slightly harder to grasp) definition of linear dependence. Consider a set of vectors and scalars . If there is a way to get with at least one , we have linearly dependent vectors. In other words, if we can get the zero vector as a linear combination of the vectors in the set, with weights that are not all zero, we have a linearly dependent set.

A set of vectors is linearly independent if none vector can be obtained as a linear combination of other vectors in the set. As you can see in the right pane, there is no way for us to combine vectors and to obtain . Again, consider a set of vectors and scalars . If the only way to get requires all , the we have linearly independent vectors. In words, the only way to get the zero vectors in by multoplying each vector in the set by .

The importance of the concepts of linear dependence and independence will become clearer in more advanced topics. For now, the important points to remember are: linearly dependent vectors contain redundant information, whereas linearly independent vectors do not.

Vector null space

Now that we know what subspaces and linear dependent vectors are, we can introduce the idea of the null space. Intuitively, the null space of a set of vectors are all linear combinations that "map" into the zero vector. Consider a set of geometric vectors , , , and as in Fig. 8. By inspection, we can see that vectors and are parallel to each other, hence, independent. On the contrary, vectors and can be obtained as linear combinations of and , therefore, dependent.

As result, with this four vectors, we can form the following two combinations that will "map" into the origin of the coordinate system, this is, the zero vector :

We will see how this idea of the null space extends naturally in the context of matrices later.

Vector norms

Measuring vectors is another important operation in machine learning applications. Intuitively, we can think about the norm or the length of a vector as the distance between its "origin" and its "end".

Norms "map" vectors to non-negative values. In this sense are functions that assign length to a vector . To be valid, a norm has to satisfy these properties (keep in mind these properties are a bit abstruse to understand):

- Absolutely homogeneous: . In words: for all real-valued scalars, the norm scales proportionally with the value of the scalar.

- Triangle inequality: . In words: in geometric terms, for any triangle the sum of any two sides must be greater or equal to the lenght of the third side. This is easy to see experimentally: grab a piece of rope, form triangles of different sizes, measure all the sides, and test this property.

- Positive definite: and . In words: the length of any has to be a positive value (i.e., a vector can't have negative length), and a length of occurs only of

Grasping the meaning of these three properties may be difficult at this point, but they probably become clearer as you improve your understanding of linear algebra.

Euclidean norm

The Euclidean norm is one of the most popular norms in machine learning. It is so widely used that sometimes is refered simply as "the norm" of a vector. Is defined as:

Hence, in two dimensions the norm is:

Which is equivalent to the formula for the hypotenuse a triangle with sides and .

The same pattern follows for higher dimensions of

In NumPy, we can compute the norm as:

x = np.array([[3],[4]])

np.linalg.norm(x, 2)

# 5.0

If you remember the first "Pythagorean triple", you can confirm that the norm is correct.

Manhattan norm

The Manhattan or norm gets its name in analogy to measuring distances while moving in Manhattan, NYC. Since Manhattan has a grid-shape, the distance between any two points is measured by moving in vertical and horizontals lines (instead of diagonals as in the Euclidean norm). It is defined as:

Where is the absolute value. The norm is preferred when discriminating between elements that are exactly zero and elements that are small but not zero.

In NumPy we compute the norm as

x = np.array([[3],[-4]])

np.linalg.norm(x, 1)

# 7.0

Is easy to confirm that the sum of the absolute values of and is .

Max norm

The max norm or infinity norm is simply the absolute value of the largest element in the vector. It is defined as:

Where is the absolute value. For instance, for a vector with elements , the

In NumPy we compute the norm as:

x = np.array([[3],[-4]])

np.linalg.norm(x, np.inf)

# 4.0

Vector inner product, length, and distance.

For practical purposes, inner product and length are used as equivalent to dot product and norm, although technically are not the same.

Inner products are a more general concept that dot products, with a series of additional properties (see here). In other words, every dot product is an inner product, but not every inner product is a dot product. The notation for the inner product is usually a pair of angle brackets as as. For instance, the scalar inner product is defined as:

In the inner product is a dot product defined as:

Length is a concept from geometry. We say that geometric vectors have length and that vectors in have norm. In practice, many machine learning textbooks use these concepts interchangeably. I've found authors saying things like "we use the norm to compute the length of a vector". For instance, we can compute the length of a directed segment (i.e., geometrical vector) by taking the square root of the inner product with itself as:

Distance is a relational concept. It refers to the length (or norm) of the difference between two vectors. Hence, we use norms and lengths to measure the distance between vectors. Consider the vectors and , we define the distance as:

When the inner product is the dot product, the distance equals to the Euclidean distance.

In machine learning, unless made explicit, we can safely assume that an inner product refers to the dot product. We already reviewed how to compute the dot product in NumPy:

x, y = np.array([[-2],[2]]), np.array([[4],[-3]])

x.T @ y

# array([[-14]])

As with the inner product, usually, we can safely assume that distance stands for the Euclidean distance or norm unless otherwise noted. To compute the distance between a pair of vectors:

distance = np.linalg.norm(x-y, 2)

print(f'L_2 distance : {distance}')

# L_2 distance : 7.810249675906656

Vector angles and orthogonality

The concepts of angle and orthogonality are also related to geometrical vectors. We saw that inner products allow for the definition of length and distance. In the same manner, inner products are used to define angles and orthogonality.

In machine learning, the angle between a pair of vectors is used as a measure of vector similarity. To understand angles let's first look at the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. Consider a pair of non-zero vectors and . The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality states that:

In words: the absolute value of the inner product of a pair of vectors is less than or equal to the products of their length. The only case where both sides of the expression are equal is when vectors are colinear, for instance, when is a scaled version of . In the 2-dimensional case, such vectors would lie along the same line.

The definition of the angle between vectors can be thought as a generalization of the law of cosines in trigonometry, which defines for a triangle with sides , , and , and an angle are related as:

We can replace this expression with vectors lengths as:

With a bit of algebraic manipulation, we can clear the previous equation to:

And there we have a definition for (cos) angle . Further, from the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality we know that must be:

This is a necessary conclusion (range between ) since the numerator in the equation always is going to be smaller or equal to the denominator.

In NumPy, we can compute the between a pair of vectors as:

x, y = np.array([[1], [2]]), np.array([[5], [7]])

# here we translate the cos(theta) definition

cos_theta = (x.T @ y) / (np.linalg.norm(x,2) * np.linalg.norm(y,2))

print(f'cos of the angle = {np.round(cos_theta, 3)}')

# cos of the angle = [[0.988]]

We get that . Finally, to know the exact value of we need to take the trigonometric inverse of the cosine function as:

cos_inverse = np.arccos(cos_theta)

print(f'angle in radiants = {np.round(cos_inverse, 3)}')

# angle in radiants = [[0.157]]

We obtain . To fo from radiants to degrees we can use the following formula:

degrees = cos_inverse * ((180)/np.pi)

print(f'angle in degrees = {np.round(degrees, 3)}')

# angle in degrees = [[8.973]]

We obtain

Orthogonality is often used interchangeably with "independence" although they are mathematically different concepts. Orthogonality can be seen as a generalization of perpendicularity to vectors in any number of dimensions.

We say that a pair of vectors and are orthogonal if their inner product is zero, . The notation for a pair of orthogonal vectors is . In the 2-dimensional plane, this equals to a pair of vectors forming a angle.

Here is an example of orthogonal vectors

x = np.array([[2], [0]])

y = np.array([[0], [2]])

cos_theta = (x.T @ y) / (np.linalg.norm(x,2) * np.linalg.norm(y,2))

print(f'cos of the angle = {np.round(cos_theta, 3)}')

# cos of the angle = [[0.]]

We see that this vectors are orthogonal as . This is equal to radiants and

cos_inverse = np.arccos(cos_theta)

degrees = cos_inverse * ((180)/np.pi)

print(f'angle in radiants = {np.round(cos_inverse, 3)}\nangle in degrees ={np.round(degrees, 3)} ')

"""

angle in radiants = [[1.571]]

angle in degrees =[[90.]]

"""

Systems of linear equations

The purpose of linear algebra as a tool is to solve systems of linear equations. Informally, this means to figure out the right combination of linear segments to obtain an outcome. Even more informally, think about making pancakes: In what proportion () we have to mix ingredients to make pancakes? You can express this as a linear equation:

The above expression describe a linear equation. A system of linear equations involve multiple equations that have to be solved simultaneously. Consider:

Now we have a system with two unknowns, and . We'll see general methods to solve systems of linear equations later. For now, I'll give you the answer: and . Geometrically, we can see that both equations produce a straight line in the 2-dimensional plane. The point on where both lines encounter is the solution to the linear system.

df = pd.DataFrame({"x1": [0, 2], "y1":[8, 3], "x2": [0.5, 2], "y2": [0, 3]})

equation1 = alt.Chart(df).mark_line().encode(x="x1", y="y1")

equation2 = alt.Chart(df).mark_line(color="red").encode(x="x2", y="y2")

equation1 + equation2

Matrices

# Libraries for this section

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import altair as alt

Matrices are as fundamental as vectors in machine learning. With vectors, we can represent single variables as sets of numbers or instances. With matrices, we can represent sets of variables. In this sense, a matrix is simply an ordered collection of vectors. Conventionally, column vectors, but it's always wise to pay attention to the authors' notation when reading matrices. Since computer screens operate in two dimensions, matrices are the way in which we interact with data in practice.

More formally, we represent a matrix with a italicized upper-case letter like . In two dimensions, we say the matrix has rows and columns. Each entry of is defined as , and . A matrix is defines as:

In Numpy, we construct matrices with the array method:

A = np.array([[0,2], # 1st row

[1,4]]) # 2nd row

print(f'a 2x2 Matrix:\n{A}')

"""

a 2x2 Matrix:

[[0 2]

[1 4]]

"""

Basic Matrix operations

Matrix-matrix addition

We add matrices in a element-wise fashion. The sum of and is defined as:

For instance:

In Numpy, we add matrices with the + operator or add method:

A = np.array([[0,2],

[1,4]])

B = np.array([[3,1],

[-3,2]])

A + B

"""

array([[ 3, 3],

[-2, 6]])

"""

np.add(A, B)

"""

array([[ 3, 3],

[-2, 6]])

"""

Matrix-scalar multiplication

Matrix-scalar multiplication is an element-wise operation. Each element of the matrix is multiplied by the scalar . Is defined as:

Consider and , then:

In NumPy, we compute matrix-scalar multiplication with the * operator or multiply method:

alpha = 2

A = np.array([[1,2],

[3,4]])

alpha * A

"""

array([[2, 4],

[6, 8]])

"""

np.multiply(alpha, A)

"""

array([[2, 4],

[6, 8]])

"""

Matrix-vector multiplication: dot product

Matrix-vector multiplication equals to taking the dot product of each column of a with each element resulting in a vector . Is defined as:

For instance:

In numpy, we compute the matrix-vector product with the @ operator or dot method:

A = np.array([[0,2],

[1,4]])

x = np.array([[1],

[2]])

A @ x

"""

array([[4],

[9]])

"""

np.dot(A, x)

"""

array([[4],

[9]])

"""

Matrix-matrix multiplication

Matrix-matrix multiplication is a dot produt as well. To work, the number of columns in the first matrix has to be equal to the number of rows in the second matrix . Hence, times to be valid. One way to see matrix-matrix multiplication is by taking a series of dot products: the 1st column of times the 1st row of , the 2nd column of times the 2nd row of , until the column of times the row of .

We define :

A compact way to define the matrix-matrix product is:

For instance

Matrix-matrix multiplication has a series of important properties:

- Associativity:

- Associativity with scalar multiplication:

- Distributivity with addition:

- Transpose of product:

It's also important to remember that matrix-matrix multiplication orders matter, this is, it is not commutative. Hence, in general, .

In NumPy, we obtan the matrix-matrix product with the @ operator or dot method:

A = np.array([[0,2],

[1,4]])

B = np.array([[1,3],

[2,1]])

A @ B

"""

array([[4, 2],

[9, 7]])

"""

np.dot(A, B)

"""

array([[4, 2],

[9, 7]])

"""

Matrix identity

An identity matrix is a square matrix with ones on the diagonal from the upper left to the bottom right, and zeros everywhere else. We denote the identity matrix as . We define as:

For example:

You can think in the inverse as playing the same role than in operations with real numbers. The inverse matrix does not look very interesting in itself, but it plays an important role in some proofs and for the inverse matrix (which can be used to solve system of linear equations).

Matrix inverse

In the context of real numbers, the multiplicative inverse (or reciprocal) of a number , is the number that when multiplied by yields . We denote this by or . Take the number . Its multiplicative inverse equals to .

If you recall the matrix identity section, we said that the identity plays a similar role than the number one but for matrices. Again, by analogy, we can see the inverse of a matrix as playing the same role than the multiplicative inverse for numbers but for matrices. Hence, the inverse matrix is a matrix than when multiplies another matrix from either the right or the left side, returns the identity matrix.

More formally, consider the square matrix . We define as matrix with the property:

The main reason we care about the inverse, is because it allows to solve systems of linear equations in certain situations. Consider a system of linear equations as:

Assuming has an inverse, we can multiply by the inverse on both sides:

And get:

Since the does not affect at all, our final expression becomes:

This means that we just need to know the inverse of , multiply by the target vector , and we obtain the solution for our system. I mentioned that this works only in certain situations. By this I meant: if and only if happens to have an inverse. Not all matrices have an inverse. When exist, we say is nonsingular or invertible, otherwise, we say it is noninvertible or singular.

The lingering question is how to find the inverse of a matrix. We can do it by reducing to its reduced row echelon form by using Gauss-Jordan Elimination. If has an inverse, we will obtain the identity matrix as the row echelon form of . I haven't introduced either just yet. You can jump to the Solving systems of linear equations with matrices if you are eager to learn about it now. For now, we relie on NumPy.

In NumPy, we can compute the inverse of a matrix with the .linalg.inv method:

A = np.array([[1, 2, 1],

[4, 4, 5],

[6, 7, 7]])

A_i = np.linalg.inv(A)

print(f'A inverse:\n{A_i}')

"""

A inverse:

[[-7. -7. 6.]

[ 2. 1. -1.]

[ 4. 5. -4.]]

"""

We can check the is correct by multiplying. If so, we should obtain the identity

I = np.round(A_i @ A)

print(f'A_i times A resulsts in I_3:\n{I}')

"""

A_i times A resulsts in I_3:

[[ 1. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 1. -0.]

[ 0. -0. 1.]]

"""

Matrix transpose

Consider a matrix . The transpose of is denoted as . We obtain as:

In other words, we get the by switching the columns by the rows of . For instance:

In NumPy, we obtain the transpose with the T method:

A = np.array([[1, 2],

[3, 4],

[5, 6]])

A.T

"""

array([[1, 3, 5],

[2, 4, 6]])

"""

Hadamard product

It is tempting to think in matrix-matrix multiplication as an element-wise operation, as multiplying each overlapping element of and . It is not. Such operation is called Hadamard product. I'm introducing this to avoid confusion. The Hadamard product is defined as

For instance:

In numpy, we compute the Hadamard product with the * operator or multiply method:

A = np.array([[0,2],

[1,4]])

B = np.array([[1,3],

[2,1]])

A * B

"""

array([[0, 6],

[2, 4]])

"""

np.multiply(A, B)

"""

array([[0, 6],

[2, 4]])

"""

Special matrices

There are several matrices with special names that are commonly found in machine learning theory and applications. Knowing these matrices beforehand can improve your linear algebra fluency, so we will briefly review a selection of 12 common matrices. For an extended list of special matrices see here and here.

Rectangular matrix

Matrices are said to be rectangular when the number of rows is to the number of columns, i.e., with . For instance:

Square matrix

Matrices are said to be square when the number of rows the number of columns, i.e., . For instance:

Diagonal matrix

Square matrices are said to be diagonal when each of its non-diagonal elements is zero, i.e., For , we have . For instance:

Upper triangular matrix

Square matrices are said to be upper triangular when the elements below the main diagonal are zero, i.e., For , we have . For instance:

Lower triangular matrix

Square matrices are said to be lower triangular when the elements above the main diagonal are zero, i.e., For , we have . For instance:

Symmetric matrix

Square matrices are said to be symmetric its equal to its transpose, i.e., . For instance:

Identity matrix

A diagonal matrix is said to be the identity when the elements along its main diagonal are equal to one. For instance:

Scalar matrix

Diagonal matrices are said to be scalar when all the elements along its main diaonal are equal, i.e., . For instance:

Null or zero matrix

Matrices are said to be null or zero matrices when all its elements equal to zero, wich is denoted as . For instance:

Echelon matrix

Matrices are said to be on echelon form when it has undergone the process of Gaussian elimination. More specifically:

- Zero rows are at the bottom of the matrix

- The leading entry (pivot) of each nonzero row is to the right of the leading entry of the row above it

- Each leading entry is the only nonzero entry in its column

For instance:

In echelon form after Gaussian Elimination becomes:

Antidiagonal matrix

Matrices are said to be antidiagonal when all the entries are zero but the antidiagonal (i.e., the diagonal starting from the bottom left corner to the upper right corner). For instance:

Design matrix

Design matrix is a special name for matrices containing explanatory variables or features in the context of statistics and machine learning. Some authors favor this name to refer to the set of variables or features in a model.

Matrices as systems of linear equations

I introduced the idea of systems of linear equations as a way to figure out the right combination of linear segments to obtain an outcome. I did this in the context of vectors, now we can extend this to the context of matrices.

Matrices are ideal to represent systems of linear equations. Consider the matrix and vectors and in . We can set up a system of linear equations as as:

This is equivalent to:

Geometrically, the solution for this representation equals to plot a set of planes in 3-dimensional space, one for each equation, and to find the segment where the planes intersect.

An alternative way, which I personally prefer to use, is to represent the system as a linear combination of the column vectors times a scaling term:

Geometrically, the solution for this representation equals to plot a set of vectors in 3-dimensional space, one for each column vector, then scale them by and add them up, tip to tail, to find the resulting vector .

The four fundamental matrix subsapces

Let's recall the definition of a subspace in the context of vectors:

- Contains the zero vector,

- Closure under multiplication,

- Closure under addition,

These conditions carry on to matrices since matrices are simply collections of vectors. Thus, now we can ask what are all possible subspaces that can be "covered" by a collection of vectors in a matrix. Turns out, there are four fundamental subspaces that can be "covered" by a matrix of valid vectors: (1) the column space, (2) the row space, (3) the null space, and (4) the left null space or null space of the transpose.

These subspaces are considered fundamental because they express many important properties of matrices in linear algebra.

The column space

The column space of a matrix is composed by all linear combinations of the columns of . We denote the column space as . In other words, equals to the span of the columns of . This view of a matrix is what we represented in Fig. 12: vectors in scaled by real numbers.

For a matrix and a vector , the column space is defined as:

In words: all linear combinations of the column vectors of and entries of an dimensional vector .

The row space

The row space of a matrix is composed of all linear combinations of the rows of a matrix. We denote the row space as . In other words, equals to the span of the rows of . Geometrically, this is the way we represented a matrix in Fig. 11: each row equation represented as planes. Now, a different way to see the row space, is by transposing . Now, we can define the row space simply as

For a matrix and a vector , the row space is defined as:

In words: all linear combinations of the row vectors of and entries of an dimensional vector .

The null space

The null space of a matrix is composed of all vectors that are map into the zero vector when multiplied by . We denote the null space as .

For a matrix and a vector , the null space is defined as:

The null space of the transpose

The left null space of a matrix is composed of all vectors that are map into the zero vector when multiplied by from the left. By "from the left", the vectors on the left of . We denote the left null space as

For a matrix and a vector , the null space is defined as:

Solving systems of linear equations with Matrices

Gaussian Elimination

When I was in high school, I learned to solve systems of two or three equations by the methods of elimination and substitution. Nevertheless, as systems of equations get larger and more complicated, such inspection-based methods become impractical. By inspection-based, I mean "just by looking at the equations and using common sense". Thus, to approach such kind of systems we can use the method of Gaussian Elimination.

Gaussian Elimination, is a robust algorithm to solve linear systems. We say is robust, because it works in general, it all possible circumstances. It works by eliminating terms from a system of equations, such that it is simplified to the point where we obtain the row echelon form of the matrix. A matrix is in row echelon form when all rows contain zeros at the bottom left of the matrix. For instance:

The values along the diagonal are the pivots also known as basic variables of the matrix. An important remark about the pivots, is that they indicate which vectors are linearly independent in the matrix, once the matrix has been reduced to the row echelon form.

There are three elementary transformations in Gaussian Elimination that when combined, allow simplifying any system to its row echelon form:

- Addition and subtraction of two equations (rows)

- Multiplication of an equation (rows) by a number

- Switching equations (rows)

Consider the following system :

We want to know what combination of columns of will generate the target vector . Alternatively, we can see this as a decomposition problem, as how can we decompose into columns of . To aid the application of Gaussian Elimination, we can generate an augmented matrix , this is, appending to on this manner:

We start by multiplying row 1 by and substracting it from row 2 as to obtain:

If we substract row 1 from row 3 as we get:

At this point, we have found the row echelon form of . If we divide row 3 by -3, We know that . By backsubsitution, we can solve for as:

Again, taking and we can solve for as:

In this manner, we have found that the solution for our system is , , and .

In NumPy, we can solve a system of equations with Gaussian Elimination with the linalg.solve method as:

A = np.array([[1, 3, 5],

[2, 2, -1],

[1, 3, 2]])

y = np.array([[-1],

[1],

[2]])

np.linalg.solve(A, y)

"""

array([[-2.],

[ 2.],

[-1.]])

"""

Which confirms our solution is correct.

Gauss-Jordan Elimination

The only difference between Gaussian Elimination and Gauss-Jordan Elimination, is that this time we "keep going" with the elemental row operations until we obtain the reduced row echelon form. The reduced part means two additionak things: (1) the pivots must be , (2) and the entries above the pivots must be . This is simplest form a system of linear equations can take. For instance, for a 3x3 matrix:

Let's retake from where we left Gaussian elimination in the above section. If we divide row 3 by -3 and row 2 by -4 as and , we get:

Again, by this point we we know . If we multiply row 2 by 3 and substract from row 1 as :

Finally, we can add 3.25 times row 3 to row 1, and substract 2.75 times row 3 to row 2, as and to get the reduced row echelon form as:

Now, by simply following the rules of matrix-vector multiplication, we get =

There you go, we obtained that , , and .

Matrix basis and rank

A set of linearly independent column vectors with elements forms a basis. For instance, the column vectors of are a basis:

"A basis for what?" You may be wondering. In the case of , for any vector . On the contrary, the column vectors for do not form a basis for :

In the case of , the third column vector is a linear combination of first and second column vectors.

The definition of a basis depends on the independence-dimension inequality, which states that a linearly independent set of vectors can have at most elements. Alternatively, we say that any set of vectors with elements is, necessarily, linearly dependent. Given that each vector in a basis is linearly independent, we say that any vector with elements, can be generated in a unique linear combination of the basis vectors. Hence, any matrix more columns than rows (as in ) will have dependent vectors. Basis are sometimes referred to as the minimal generating set.

An important question is how to find the basis for a matrix. Another way to put the same question is to found out which vectors are linearly independent of each other. Hence, we need to solve:

Where are the column vectors of . We can approach this by using Gaussian Elimination or Gauss-Jordan Elimination and reducing to its row echelon form or reduced row echelon form. In either case, recall that the pivots of the echelon form indicate the set of linearly independent vectors in a matrix.

NumPy does not have a method to obtain the row echelon form of a matrix. But, we can use Sympy, a Python library for symbolic mathematics that counts with a module for Matrices operations.SymPy has a method to obtain the reduced row echelon form and the pivots, rref.

from sympy import Matrix

A = Matrix([[1, 0, 1],

[0, 1, 1]])

B = Matrix([[1, 2, 3, -1],

[2, -1, -4, 8],

[-1, 1, 3, -5],

[-1, 2, 5, -6],

[-1, -2, -3, 1]])

A_rref, A_pivots = A.rref()

print('Reduced row echelon form of A:')

# Reduced row echelon form of A:

print(f'Column pivots of A: {A_pivots}')

# Column pivots of A: (0, 1)

B_rref, B_pivots = B.rref()

print('Reduced row echelon form of B:')

# Reduced row echelon form of B:

print(f'Column pivots of A: {B_pivots}')

# Column pivots of A: (0, 1, 3)

For , we found that the first and second column vectors are the basis, whereas for is the first, second, and fourth.

Now that we know about a basis and how to find it, understanding the concept of rank is simpler. The rank of a matrix is the dimensionality of the vector space generated by its number of linearly independent column vectors. This happens to be identical to the dimensionality of the vector space generated by its row vectors. We denote the rank of matrix as or .

For an square matrix (i.e., ), we say is full rank when every column and/or row is linearly independent. For a non-square matrix with (i.e., more rows than columns), we say is full rank when every row is linearly independent. When (i.e., more columns than rows), we say is full rank when every column is linearly independent.

From an applied machine learning perspective, the rank of a matrix is relevant as a measure of the information content of the matrix. Take matrix from the example above. Although the original matrix has 5 columns, we know is rank 4, hence, it has less information than it appears at first glance.

Matrix norm

As with vectors, we can measure the size of a matrix by computing its norm. There are multiple ways to define the norm for a matrix, as long it satisfies the same properties defined for vectors norms: (1) absolutely homogeneous, (2) triangle inequality, (3) positive definite (see vector norms section). For our purposes, I'll cover two of the most commonly used norms in machine learning: (1) Frobenius norm, (2) max norm, (3) spectral norm.

Note: I won't cover the spectral norm just yet, because it depends on concepts that I have not introduced at this point.

Frobenius norm

The Frobenius norm is an element-wise norm named after the German mathematician Ferdinand Georg Frobenius. We denote this norm as . You can thing about this norm as flattening out the matrix into a long vector. For instance, a matrix would become a vector with entries. We define the Frobenius norm as:

In words: square each entry of , add them together, and then take the square root.

In NumPy, we can compute the Frobenius norm as with the linal.norm method ant fro as the argument:

A = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]])

np.linalg.norm(A, 'fro')

# 16.881943016134134

Max norm

The max norm or infinity norm of a matrix equals to the largest sum of the absolute value of row vectors. We denote the max norm as . Consider . We define the max norm for as:

This equals to go row by row, adding the absolute value of each entry, and then selecting the largest sum.

In Numpy, we compute the max norm as:

A = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]])

np.linalg.norm(A, np.inf)

# 24.0

In this case, is easy to see that the third row has the largest absolute value.

Spectral norm

To understand this norm, is necessary to first learn about eigenvectors and eigenvalues, which I cover later.

The spectral norm of a matrix equals to the largest singular value . We denote the spectral norm as . Consider . We define the spectral for as:

In Numpy, we compute the max norm as:

A = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]])

np.linalg.norm(A, 2)

# 16.84810335261421

Linear and affine mappings

# Libraries for this section

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import altair as alt

alt.themes.enable('dark')

# ThemeRegistry.enable('dark')

Linear mappings

Now we have covered the basics of vectors and matrices, we are ready to introduce the idea of a linear mapping. Linear mappings, also known as linear transformations and linear functions, indicate the correspondence between vectors in a vector space and the same vectors in a different vector space . This is an abstract idea. I like to think about this in the following manner: imagine there is a multiverse as in Marvel comics, but instead of humans, aliens, gods, stars, galaxies, and superheroes, we have vectors. In this context, a linear mapping would indicate the correspondence of entities (i.e., planets, humans, superheroes, etc) between universes. Just imagine us, placidly existing in our own universe, and suddenly a linear mapping happens: our entire universe would be transformed into a different one, according to whatever rules the linear mapping has enforced. Now, switch universes for vector spaces and us by vectors, and you'll get the full picture.

So, linear mappings transform vector spaces into others. Yet, such transformations are constrained to a spefic kind: linear ones. Consider a linear mapping and a pair of vectors and . To be valid, a linear mapping must satisfies these rules:

In words:

- The transformation of the sum of the vectors must be equal to taking the transformation of each vector individually and then adding them up.

- The transformation of a scaled version of a vector must be equal to taking the transformation of the vector first and then scaling the result.

The two properties above can be condenced into one, the superposition property:

As a result of satisfying those properties, linear mappings preserve the structure of the original vector space. Imagine a vector space , like a grid on lines in a cartesian plane. Visually, preserving the structure of the vector space after a mapping means to: (1) the origin of the coordinate space remains fixed, and (2) the lines remain lines and parallel to each other.

In linear algebra, linear mappings are represented as matrices and performed by matrix multiplication. Take a vector and a matrix . We say that when multiplies , the matrix transform the vector into another one:

The typicall notation for a linear mapping is the same we used for functions. For the vector spaces and , we indicate the linear mapping as

Examples of linear mappings

Let's examine a couple of examples of proper linear mappings. In general, dot products are linear mappings. This should come as no surprise since dot products are linear operations by definition. Dot products sometimes take special names, when they have a well-known effect on a linear space. I'll examine two simple cases: negation and reversal. Keep in mind that although we will test this for one vector, this mapping work on the entire vector space (i.e., the span) of a given dimensionality.

Negation matrix

A negation matrix returns the opposite sign of each element of a vector. It can be defined as:

This is, the negative identity matrix. Consider a pair of vectors and , and the negation matrix . Let's test the linear mapping properties with NumPy:

x = np.array([[-1],

[0],

[1]])

y = np.array([[-3],

[0],

[2]])

T = np.array([[-1,0,0],

[0,-1,0],

[0,0,-1]])

We first test :

left_side_1 = T @ (x+y)

right_side_1 = (T @ x) + (T @ y)

print(f"Left side of the equation:\n{left_side_1}")

print(f"Right side of the equation:\n{right_side_1}")

"""

Left side of the equation:

[[ 4]

[ 0]

[-3]]

Right side of the equation:

[[ 4]

[ 0]

[-3]]

"""

Hence, we confirm we get the same results.

Let's check the second property

alpha = 2

left_side_2 = T @ (alpha * x)

right_side_2 = alpha * (T @ x)

print(f"Left side of the equation:\n{left_side_2}")

print(f"Right side of the equation:\n{right_side_2}")

"""

Left side of the equation:

[[ 2]

[ 0]

[-2]]

Right side of the equation:

[[ 2]

[ 0]

[-2]]

"""

Again, we confirm we get the same results for both sides of the equation

Reversal matrix

A reversal matrix returns reverses the order of the elements of a vector. This is, the last become the first, the second to last becomes the second, and so on. For a matrix in is defined as:

In general, it is the identity matrix but backwards, with ones from the bottom left corner to the top right corern. Consider a pair of vectors and , and the reversal matrix . Let's test the linear mapping properties with NumPy:

x = np.array([[-1],

[0],

[1]])

y = np.array([[-3],

[0],

[2]])

T = np.array([[0,0,1],

[0,1,0],

[1,0,0]])

We first test :

x_reversal = T @ x

y_reversal = T @ y

left_side_1 = T @ (x+y)

right_side_1 = (T @ x) + (T @ y)

print(f"x before reversal:\n{x}\nx after reversal \n{x_reversal}")

print(f"y before reversal:\n{y}\ny after reversal \n{y_reversal}")

print(f"Left side of the equation (add reversed vectors):\n{left_side_1}")

print(f"Right side of the equation (add reversed vectors):\n{right_side_1}")

"""

x before reversal:

[[-1]

[ 0]

[ 1]]

x after reversal

[[ 1]

[ 0]

[-1]]

y before reversal:

[[-3]

[ 0]

[ 2]]

y after reversal

[[ 2]

[ 0]

[-3]]

Left side of the equation (add reversed vectors):

[[ 3]

[ 0]

[-4]]

Right side of the equation (add reversed vectors):

[[ 3]

[ 0]

[-4]]

"""

This works fine. Let's check the second property

alpha = 2

left_side_2 = T @ (alpha * x)

right_side_2 = alpha * (T @ x)

print(f"Left side of the equation:\n{left_side_2}")

print(f"Right side of the equation:\n{right_side_2}")

"""

Left side of the equation:

[[ 2]

[ 0]

[-2]]

Right side of the equation:

[[ 2]

[ 0]

[-2]]

"""

Examples of nonlinear mappings

As with most subjects, examining examples of what things are not can be enlightening. Let's take a couple of non-linear mappings: norms and translation.

Norms

This may come as a surprise, but norms are not linear transformations. Not "some" norms, but all norms. This is because of the very definition of a norm, in particular, the triangle inequality and positive definite properties, colliding with the requirements of linear mappings.

First, the triangle inequality defines: . Whereas the first requirement for linear mappings demands: . The problem here is in the condition, which means adding two vectors and then taking the norm can be less than the sum of the norms of the individual vectors. Such condition is, by defnition, not allowed for linear mappings.

Second, the positive definite defines: and . Put simply, norms have to be a postive value. For instance, the norm of , instead of . But, the second property for linear mappings requires . Hence, it fails when we multiply by a negative number (i.e., it can preserve the negative sign).

Translation

Translation is a geometric transformation that moves every vector in a vector space by the same distance in a given direction. Translation is an operation that matches our everyday life intuitions: move a cup of coffee from your left to your right, and you would have performed translation in space.

Contrary to what we have seen so far, the translation matrix is represented with homogeneous coordinates instead of cartesian coordinates. Put simply, the homogeneous coordinate system adds a extra at the end of vectros. For instance, the vector in cartesian coordinates:

Becomes the following in homogeneous coordinates:

In fact, the translation matrix for the general case can't be represented with cartesian coordinates. Homogeneous coordinates are the standard in fields like computer graphics since they allow us to better represent a series of transformations (or mappings) like scaling, translation, rotation, etc.

A translation matrix in can be denoted as:

Where and are the values added to each dimension for translation. For instance, consider . If we want translate this units in the first dimension, and units in the second dimension, we first transfor the vector to homogeneous coordinates , and then perfom matrix-vector multiplication as usual:

The first two vectors in the translation matrix simple reproduce the original vector (i.e., the identity), and the third vector is the one actually "moving" the vectors.

Translation is not a linear mapping simply because does not hold. In the case of translation , which invalidates the operation as a linear mapping. This type of mapping is known as an affine mapping or transformation, which is the topic I'll review next.

Affine mappings

The simplest way to describe affine mappings (or transformations) is as a linear mapping + translation. Hence, an affine mapping takes the form of:

Where is a linear mapping or transformation and is the translation vector.

If you are familiar with linear regression, you would notice that the above expression is its matrix form. Linear regression is usually analyzed as a linear mapping plus noise, but it can also be seen as an affine mapping. Alternative, we can say that is a linear mapping if and only if .

From a geometrical perspective, affine mappings displace spaces (lines or hyperplanes) from the origin of the coordinate space. Consequently, affine mappings do not operate over vector spaces as the zero vector condition does not hold anymore. Affine mappings act onto affine subspaces, that I'll define later in this section.

Affine combination of vectors

We can think in affine combinations of vectors, as linear combinations with an added constraint. Let's recall de definitoon for a linear combination. Consider a set of vectors and scalars , then a linear combination is:

For affine combinations, we add the condition:

In words, we constrain the sum of the weights to . In practice, this defines a weighted average of the vectors. This restriction has a palpable effect which is easier to grasp from a geometric perspective.

Fig. 15 shows two affine combinations. The first combination with weights and , which yields the midpoint between vectors and . The second combination with weights and (add up to ), which yield a point over the vector . In both cases, we have that the resulting vector lies on the same line. This is a general consequence of constraining the sum of the weights to : every affine combination of the same set of vectors will map onto the same space.

Affine span

The set of all linear combinations, define the the vector span. Similarly, the set of all affine combinations determine the affine span. As we saw in Fig. 15, every affine of vectors and maps onto the line . More generally, we say that the affine span of vectors is:

Again, in words: the affine span is the set of all linear combinations of the vector set, such that the weights add up to and all weights are real numbers. Hence, the fundamental difference between vector spaces and affine spaces, is the former will span the entire space (assuming independent vectors), whereas the latter will span a line.

Let's consider three cases in : (1) three linearly independent vectors; (2) two linearly independent vectors and one dependent vector; (3) three linearly dependent vectors. In case (1), the affine span is the 2-dimensional plane containing those vectors. In case (2), the affine space is a line. Finally, in case (3), the span a single point. This may not be entirely obvious, so I encourage you to draw and the three cases, take the affine combinations and see what happens.

Affine space and subspace

In simple terms, affine spaces are translates of vector spaces, this is, vector spaces that have been offset from the origin of the coordinate system. Such a notion makes sound affine spaces as a special case of vector spaces, but they are actually more general. Indeed, affine spaces provide a more general framework to do geometric manipulation, as they work independently of the choice of the coordinate system (i.e., it is not constrained to the origin). For instance, the set of solutions of the system of linear equations (i.e., linear regression), is an affine space, not a linear vector space.

Consider a vector space , a vector , and a subset . We define an affine subspace as:

Further, any point, line, plane, or hyperplane in that does not go through the origin, is an affine subspace.

Affine mappings using the augmented matrix

Consider the matrix , and vectors

We can represent the system of linear equations:

As a single matrix vector multiplication, by using an augmented matrix of the form:

This form is known as the affine transformation matrix. We made use of this form when we exemplified translation, which happens to be an affine mapping.

Special linear mappings

There are several important linear mappings (or transformations) that can be expressed as matrix-vector multiplications of the form . Such mappings are common in image processing, computer vision, and other linear applications. Further, combinations of linear and nonlinear mappings are what complex models as neural networks do to learn mappings from inputs to outputs. Here we briefly review six of the most important linear mappings.

Scaling

Scaling is a mapping of the form , with . Scaling stretches by a factor when , shrinks when , and reverses the direction of the vector when . For geometrical objects in Euclidean space, scaling changes the size but not the shape of objects. An scaling matrix in takes the form:

Where are the scaling factors.

Let's scale a vector using NumPy. We will define a scaling matrix , a vector to scale, and then plot the original and scaled vectors with Altair.

A = np.array([[2.0, 0],

[0, 2.0]])

x = np.array([[0, 2.0,],

[0, 4.0,]])

To scale , we perform matrix-vector multiplication as usual

y = A @ x

z = np.column_stack((y,x))

df = pd.DataFrame({'dim-1': z[0], 'dim-2':z[1], 'type': ['tran', 'tran', 'base', 'base']})

df

| dim-1 | dim-2 | type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | tran |

| 1 | 4.0 | 8.0 | tran |

| 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | base |

| 3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | base |

We see that the resulting scaled vector ('tran') is indeed two times the original vector ('base'). Now let's plot. The light blue line solid line represents the original vector, whereas the dashed orange line represents the scaled vector.

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_line(opacity=0.8).encode(

x='dim-1',

y='dim-2',

color='type',

strokeDash='type')

chart

Reflection

Reflection is the mirror image of an object in Euclidean space. For the general case, reflection of a vector through a line that passes through the origin is obtained as:

where are radians of inclination with respect to the horizontal axis. I've been purposely avoiding trigonometric functions, so let's examine a couple of special cases for a vector in (that can be extended to an arbitrary number of dimensions).

Reflection along the horizontal axis, or around the line at from the origin:

Reflection along the vertical axis, or around the line at from the origin:

Reflection along the line where the horizontal axis equals the vertical axis, or around the line at from the origin:

Reflection along the line where the horizontal axis equals the negative of the vertical axis, or around the line at from the origin:

Let's reflect a vector using NumPy. We will define a reflection matrix , a vector to reflect, and then plot the original and reflected vectors with Altair.

# rotation along the horiontal axis

A1 = np.array([[1.0, 0],

[0, -1.0]])

# rotation along the vertical axis

A2 = np.array([[-1.0, 0],

[0, 1.0]])

# rotation along the line at 45 degrees from the origin

A3 = np.array([[0, 1.0],

[1.0, 0]])

# rotation along the line at -45 degrees from the origin

A4 = np.array([[0, -1.0],

[-1.0, 0]])

x = np.array([[0, 2.0,],

[0, 4.0,]])

y1 = A1 @ x

y2 = A2 @ x

y3 = A3 @ x

y4 = A4 @ x